Guilherme S. Toledo de Carvalho

Laboratório de Ecologia e Evolução de Mar Profundo / Instituto Oceanográfico da Universidade de São Paulo, Brazil

Instagram: @gilermoesponia

Contact: guilherme.toledo@usp.br

What has been your personal journey into the deep-sea? (Did you always know this is what you wanted to do, or start out on a completely different path?) In other words, what unique journey led you to where you are now?

Near the end of my Bachelor’s degree in biology I took a class with my current Master’s degree advisor, Paulo Sumida. I had never thought about working in the deep sea, but had always found it profoundly interesting. I reached out to the professor, who has a lab that mainly focuses on deep-sea ecology and evolution, and they happened to have a project on wood-boring bivalves. I’ve always loved molluscs – specifically gastropods – but now, after studying with such an interesting group, bivalves have grown on me.

Some of the previous work I was involved in included cephalopod reproduction strategies and morphology, and freshwater fish in the Amazonian basin.

What is your current research question and why are you interested in this topic?

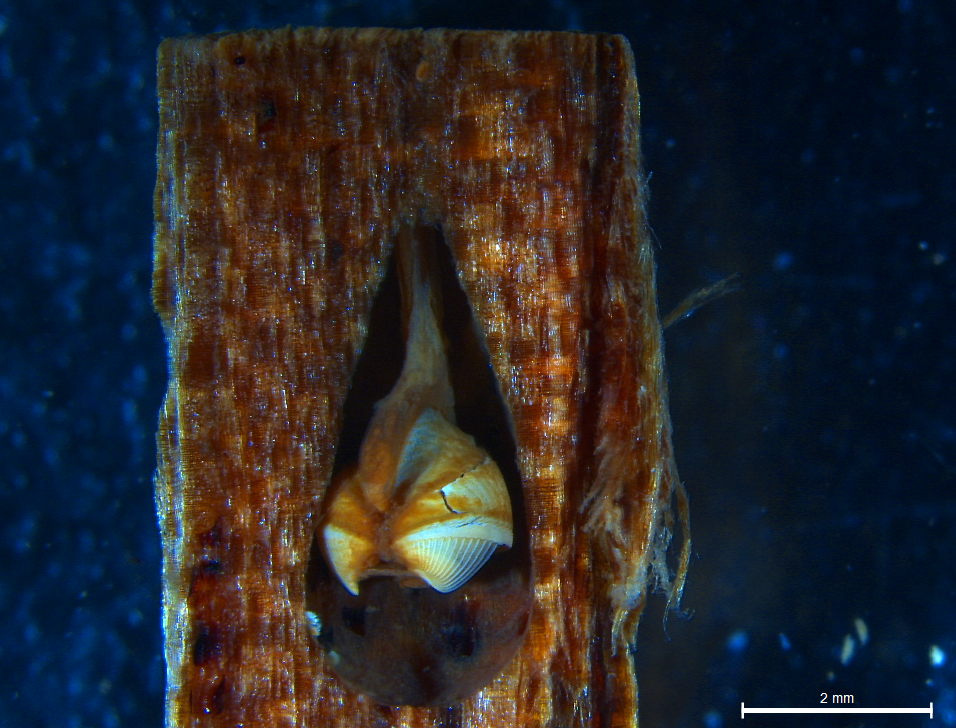

I am investigating wood-eating or -boring bivalves of the deep Southwestern Atlantic, off the coast of Santa Catarina, Brazil. Wood is alien in the deep sea. It is transported from terrestrial environments (tropical storms, landslides, etc), gets saturated with water, and sinks. Then it is consumed or buried in the sediment. I am assessing the composition of the Xylophagaidae family – wood-boring bivalves mostly restricted to the deep-sea- in the basin and if it changes with depth and wood species, formally describing any new species and genera, and exploring phylogenetic relationships. To do this we deployed wood blocks, alongside control material.

I’m interested in this topic because, in general, the South Atlantic is understudied and needs more assessments. Every time we go out, there are high abundances and diversity of species in the wood samples. I think that it may be related to the vast forests along the Brazilian coast, supplying significant amounts and varieties of wood. It’s important to understand the fate of woodfalls, because they contain significant amounts of carbon and we don’t understand how much of that carbon is sequestered versus up taken into the trophic web. Understanding those things better would give us insights into the global carbon cycle and what role Xylophagaidae play in that cycle.

What have been some challenges in your work or in studying the deep sea in general? Has your research turned out how you expected?

Some of the tasks required by my research can be quite repetitive. Especially what has to be done to process the wood after recovering it from the field experiments. I didn’t realize how much carpentry would go into deep-sea science!

My research has turned out very different than I expected. Beyond working with novel techniques, like CT scans, I have had to learn a lot more taxonomy than I was expecting. Sometimes we find shallow water species mixed up in deep-sea trawl experiments and there have been many other invertebrates on the wood blocks besides the Xylophagaidae, which I have had to learn to identify as well.

Why is this work important to you and society as a whole?

My research is important to increase our understanding of the biodiversity in a large but poorly explored, even by deep sea standards, region of the ocean. The work can also be used to better understand the global carbon cycle and in turn further our understanding of climate change.

I also think that wood-boring bivalves can expand the horizon of people outside of academia, which I love to do. It’s an understandable but completely alien form of life:, not only there is wood in the deep sea, but a whole family of clams eats it. I think that can excite people about future discoveries.

Because we are such an international organization, can you describe what the deep-sea science community is like in your region?

I wish the deep-sea research group was bigger in Brazil. But I also want the international community to know that the few labs that do exist do lots and lots of good work. Even labs that are not focused on the deep sea will occasionally do projects in the deep. I want more people to know about the work that is being done and that there are many opportunities for collaborations and future research in the region, which could bring to light data with global impacts.

What is your current position (student, researcher, government, non-profit etc) and what do you like about your current role in deep-sea science?

I am currently working on my Master’s at the Instituto Oceanográfico da Universidade de São Paulo (Oceanographic Institute of the University of São Paulo, IOUSP). I like working there because, in general, Brazil does not have a lot of research funds compared to other countries. But our institution has a decent infrastructure and manages to raise a lot of public and private collaborations, compared to other institutions. The researchers here do a lot with those funds, and this leads to there being a strong network of researchers at and out of IOUSP. There is always someone who knows someone, and there is always someone who can help you out with a question or challenge you are dealing with.

What advice could you offer to aspiring deep-sea biologists?

Deep sea research is cool. It’s hard to find the mystery of the deep sea uninteresting; it’s extremely alien but on the same planet. So, my advice is to never be bored: there is always something interesting to learn. When you think you have stagnated, there are always new pathways or avenues to explore. The work isn’t always easy; especially in the academic field, you can work very hard, and it can be a large physical and mental toll. But there is still a lot to do and discover and it can also be personally and mentally rewarding. There are few researchers working in the field, so we have to help each other, collaborate, and build strong networks.

What is the biggest challenge or project you look forward to addressing in the future?

I want to better understand the role that woodfalls and wood-boring organisms play in the global carbon cycle. As the impacts of climate change become more prominent, we need to fully understand how the carbon cycle is working. Where we are storing carbon, how much we are storing, and how much storage might be lost if those habitats are disturbed by increasing human activities.

I would love to do more work like what I am currently doing at more locations in the South Atlantic, and incorporate more molecular sequences to neglected deep-sea species.

What is your favourite thing about the deep sea?

My favourite thing about the deep sea is how vast it is; it is the great unknown. I feel like every time I talk to any deep-sea researcher, I always find out about something I have never heard of or imagined before, sometimes completely alien concepts. It’s a humbling subject, which reminds us that we don’t know everything and there are always new things to learn.

Please list any hashtags or websites you would like to include with this post.

Our lab website: http://lamp.io.usp.br/index.php/en/

My Instagram: @gilermoesponia

My institutional email: guilherme.toledo@usp.br

#organicfalls #Xylophaga #LATAMScience #LAMP