Loïc Van Audenhaege

Ifremer/Laboratoire Environnement Profond

Twitter: @DeepSea_LVA, Research Gate

Contact: Loic.Van.Audenhaege@ifremer.fr/loic.vanaudenhaege@gmail.com

What has been your personal journey into the deep-sea? (Did you always know this is what you wanted to do, or start out on a completely different path?)In other words, what unique journey led you to where you are now?

Let’s go back 15 years ago. When aged around 12, I remember this day at the library I borrowed that book in French called “Abysses” by Claire Nouvian. The photographs of that book pictured weird-looking creatures that immediately unleashed my curiosity: “How do they stand such high pressure?”, “How long do they live?”, “How were these pictures taken?”. However, nobody around me was able to provide me satisfying answers about that unfamiliar world… I started investigating in books and on the Internet, but then, my interest and questions never stopped growing since that day at the library. Eleven years later, I graduated from a master’s program in bioengineering in Belgium (UCLouvain) and I enrolled a marine biology master’s program (IMBRSEA). The later provided me opportunities to work on cold-water coral and hydrothermal vent ecosystems in labs around the World and to participate to two research cruises.

What is your current research question and why are you interested in this topic?

Two years ago, I enrolled at the Deep-Sea Laboratory of the Ifremer Institute (Brest, France) as a PhD student. My PhD aims to improve our ecological knowledge on hydrothermal communities at the Lucky Strike vent field (-1700 m). The primary goal of my PhD consists in describing the environmental and biotic factors shaping temporal dynamics of hydrothermal assemblages and to assess their relative role at three different study scales. In summary, my work focusses on monitoring assemblage distribution through time and identifying the factors responsible for any variability (environmental modifications and biotic interactions). All this work involves the use of underwater cameras and chemical sensors mounted on remotely operated vehicles and deep-sea observatories. For instance, I recently investigated the short-term and long-term dynamics characterizing vent mussel assemblages using daily video sequences and 3D reconstructions of hydrothermal edifices.

What have been some challenges in your work or in studying the deep sea in general? Has your research turned out how you expected?

Understanding the ecology of the deep-sea benthos in a non-invasive and efficient manner, such as using imagery or acoustic data collected by underwater vehicles or deep-sea observatories, has been growing for the past decades. Throughout different studies, I have been challenged to develop and improve workflows in order to boost the accuracy and the level of details of the results obtained from these large datasets and to translate them into meaningful ecological insights.

Why is this work important to you and society as a whole?

Nature is full of biological networks and adaptations that inspired many of existing applications. The deep-sea realm may be one of the largest library on Earth. Still, it remains the least explored. However, some deep-sea ecosystems are already threatened by human activities. Therefore, studying the functional ecology of the fauna with appropriate sampling and analytical means are therefore at importance, not only to develop fundamental concepts of ecology, but also to build sustainable conservation plans as well. Last but not least, many ecosystem services we benefit every day without even noticing it rely directly or indirectly on deep-sea ecosystems.

What advice could you offer to aspiring deep-sea biologists?

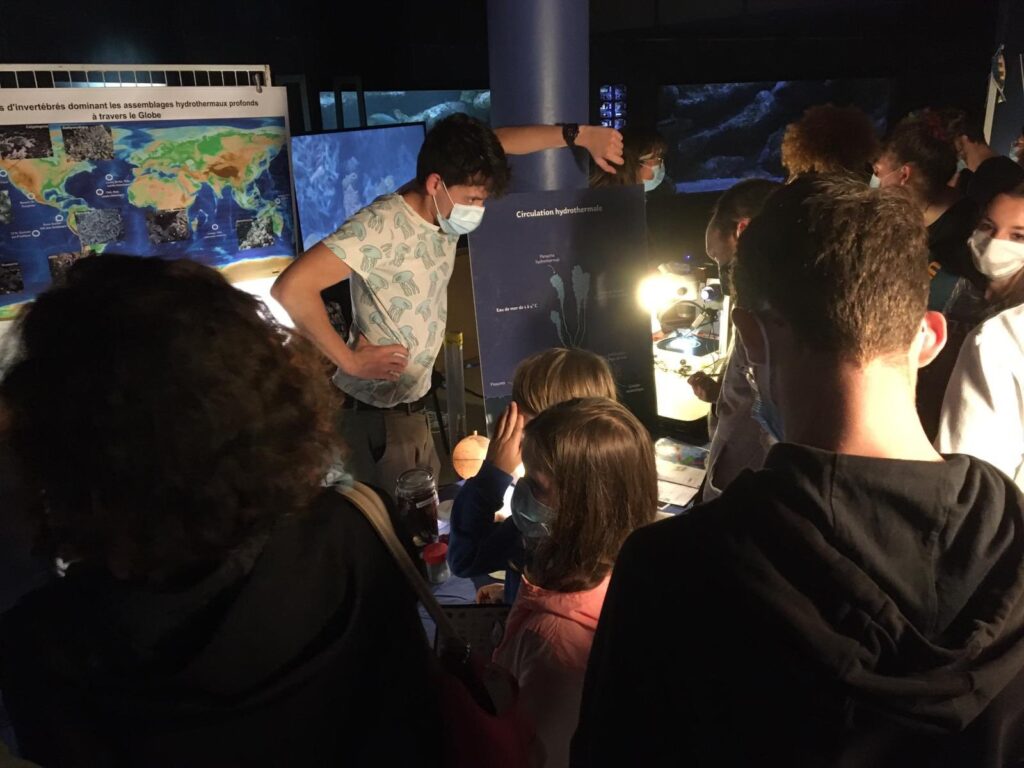

I must acknowledge the “deep-sea club” sometimes appears difficult to enter from the outside. Do not let any opportunities without consideration, get out of your comfort zone by attending any events possible, etc. With perseverance and self-investment, you will find your way through this research domain and even better, you will meet inspiring colleagues to work with.

What is the biggest challenge or project you look forward to addressing in the future?

The remoteness and darkness of the deep sea is the biggest challenge that always constrain data acquisition. I often deal with ambitious datasets that require challenging data processing to dig out relevant findings. However, in my opinion, that challenge also remains an open door to develop and apply innovative ideas and analyses. For all these reasons, I sincerely hope my future career will consist in instructive and multidisciplinary research involving synergic interactions with my future colleagues. The very last challenge remains also to share our research with the people and to connect them with deep-sea ecosystems.

What is your favorite thing about the deep sea?

The adaptations and the interactions of deep-sea living organisms are constantly surprising me because of their diversity. Still, these animals hold many secrets remaining difficult to unravel due to the remoteness of their habitats. In my opinion, it also remains a great motivation to study such ecosystems as the daily life of deep-sea organisms is constrained by environmental factors that are highly different than what we are used to experience on land. Last but not least, I particularly like to attend data collection on board, especially when achieved by underwater vehicles. To me, it remains a fascinating journey to perform deep-sea scientific surveys.