Katie Bigham

Victoria University of Wellington & National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research, New Zealand

Twitter; ResearchGate

What has been your personal journey into the deep-sea? (Did you always know this is what you wanted to do, or start out on a completely different path?) In other words, what unique journey led you to where you are now?

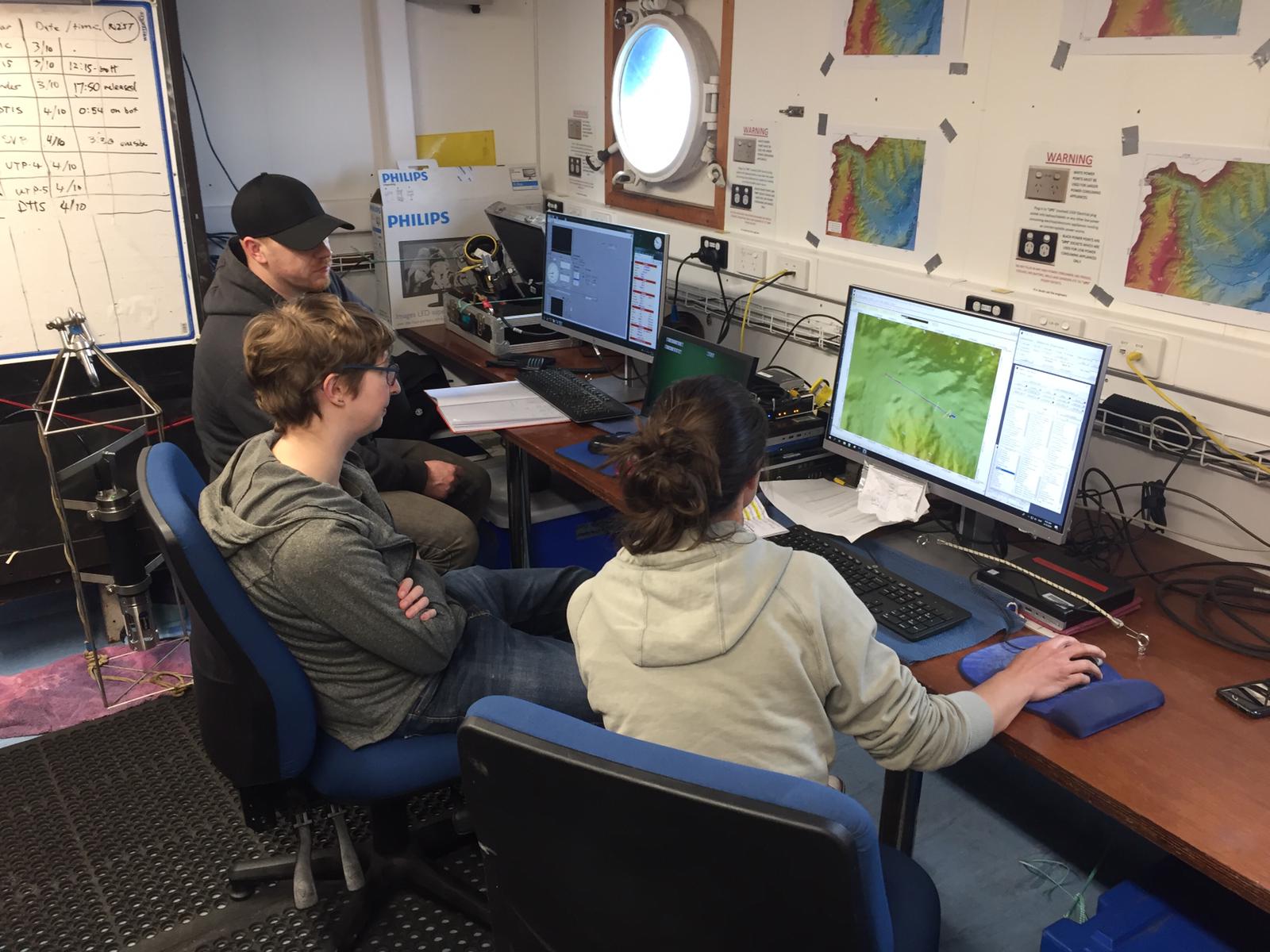

I grew up sailing, fishing, and swimming in the ocean and waterways of Washington state in the USA. Despite this aquatic association, I never considered marine sciences as something I could actually make a career of. An opportunity to participate in a research cruise during my first year at the University of Washington changed all of that, and led to me working for the Ocean Observatories Initiative’s Regional Cabled Array for two years after I graduated with a BSc in Oceanography. My time at university and working gave me the chance to experience research from the coastline to the deep sea.

What is your current research question and why are you interested in this topic?

My current project and the focus of my PhD is to understand the impacts of a large-scale turbidity flow (underwater avalanche) on the deep-sea benthic community of Kaikōura Canyon, off the coast of Aotearoa/New Zealand. Once one of the most productive deep-sea environments ever measured, the community was apparently wiped out following the turbidity flow triggered by the 2016 Kaikōura Earthquake. Using images, multibeam bathymetry, and sediment cores collected before and after the turbidity flow, my project aims to see if and how this community can recover from a large-scale disturbance. To get as broad an understanding as possible, I’m looking at responses across the size spectrum of animals: meio-, macro-, and megafauna.

What have been some challenges in your work or in studying the deep sea in general? Has your research turned out how you expected?

For this project one of biggest challenges has been, surprisingly, having a lot of samples to choose from. Deep-sea research is often expensive and time consuming, so when scientists have a chance to take samples, they tend to collect whatever they can. Since my PhD is part of a larger project to understand the Kaikōura Canyon and turbidity flow as a whole, I’ve had a plethora of samples to choose from and have had to spend time really thinking about the questions I’m trying to answer so that I focus on finding the best samples to answer them.

Why is this work important to you and society as a whole?

For me this project is interesting because the before and after turbidity-flow time series is unique, and with data from all size classes in the benthic community it is a great opportunity to study the benthic community’s resilience to turbidity flows. The event can also be used as a proxy for other large-scale disturbances in the deep sea, like seabed mining. Additionally, Kaikoura Canyon is a major feature in the Hikurangi Marine Reserve, which is an important part of New Zealand’s network of marine protected areas. Understanding the impact of the turbidity flow on the canyon community in the reserve can allow for better management of the reserve network as a whole.

Because we are such an international organization, can you describe what the deep-sea science community is like in your region?

Having participated in the deep-sea science community in both the USA and Aotearoa/New Zealand, the best description I have for the community is small. However, this also means that the deep-sea science community in both is highly interconnected at a regional and international level, which made it possible for me to find opportunities like my PhD project.

What is your current position (student, researcher, government, non-profit etc) and what do you like about your current role in deep-sea science?

I am a PhD student at Victoria University of Wellington and the National Institute of Atmospheric and Water Research (NIWA) in Aotearoa/New Zealand. Being involved in research at both a university and a government research institution has been a great opportunity to learn about what research is out there, what other people have gone on to do with their degrees, and where my degree might take me someday.

What advice could you offer to aspiring deep-sea biologists?’

Get involved! Going to sea was an important way to do that for me, but many of the ships livestream their activities so you can participate from land. A silver-lining of the pandemic has been that many organizations have been making their deep-sea seminars, events, and even art available online. Make the most of this new opportunity.

What is the biggest challenge or project you look forward to addressing in the future?

I’m interested in understanding how life survives in harsh marine environments and how these adaptations do or don’t provide resilience to natural and anthropogenic stressors. These questions require studies at the intersection of biology, chemistry, and geology which is a space that excites me. I’m also excited to find ways of better utilizing novel technological advances such as fibre optically cabled arrays and machine learning to improve our understanding of the deep sea.

What is your favourite thing about the deep sea?

That it is constantly surprising me! Even returning to the same site year after year or analysing weeks of imagery from the deep sea, I will still see something new or unexpected that leaves me full of wonder.